Whisky’s Other Influencer: Mother Nature

Learn Whisky, Opinion

When we talk about variation of flavour in whisky, the two subjects that come up most frequently are cask and time. Whether a whisky was matured for three years or twenty, in an ex-Bourbon hogshead or Sherry puncheon, is vital to how the final product turns out.

However, if cask and time were the only influencers, whisky would be an incredibly boring category. In truth, no two drams are the same – and every tiny detail of the whisky-making process has an effect on how it will taste when it finally hits your glass.

Here, we’ll be looking at one of whisky’s lesser-known influencers: Mother Nature. As Rachel Barrie of BenRiach succinctly explains: “A whisky is like a person. You are affected by where you live, where you come from, the cultures you pick up, the environment, the nature of anything.” From barley type, to peat influence, to temperature, whisky is very much a product of its environment.

Barley

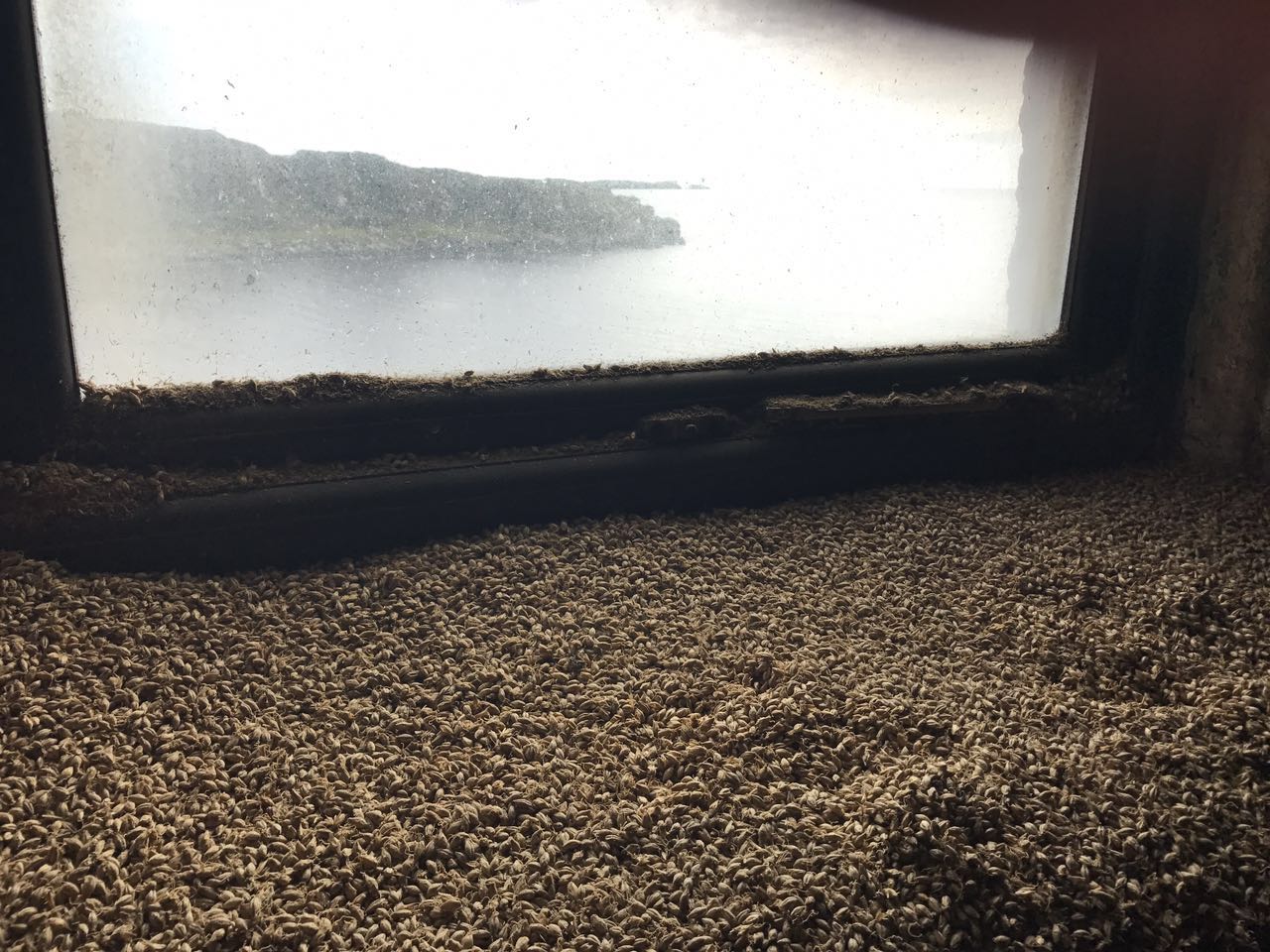

The effect of barley on a whisky’s final taste is vastly underestimated. Since Scotland doesn’t grow enough of the grain to satisfy the demand for whisky production, a considerable amount is imported from Europe and further afield. In the interest of efficiency, distillers tend to opt for varieties that produce the most amount of fermentable sugar during malting.

However, in recent years some distilleries have been experimenting with barley of specific varieties, and grown in different areas, to give differing flavours and textures.

Bruichladdich’s yearly Islay Barley releases, for example, are notably oilier and more mouthfilling than their standard Classic Laddie, and each release differs depending on the farms on which the barley is grown: Islay Barley 2007, from a coastal field with salty soils, has a distinct saline note to it, whereas the 2009 release from central fields brings out more sweet, malty cereal notes.

Furthermore, distilleries such as Amrut and Paul John in India use native varieties of ‘six-row’ barley: higher in protein and lower in starch than the ‘two-row’ types that are most commonly used to make whisky, they give a sharper, grainier flavour, with less round maltiness.

Bruichladdich have also created limited-release whiskies made from Bere barley, a fast-growing, low-yielding six-row barley that grows on Orkney, thought to be brought over by the Vikings in the 9th century. The whisky is textural, fruity and honeyed, almost sweet-seeming.

Peat

Peatiness is perhaps the most divisive flavour profile in whisky. Some people fall in love with peated whisky on their first sip of Lagavulin; however, for many others, it takes a few different drams to begin to appreciate the wildly different flavours that peat can deliver.

Peat bogs grow all over Scotland, and where a distillery sources their peat from affects the flavour tremendously. Islay bogs are heavy in sea-based vegetation and creosote, giving that medicinal, iodine note so apparent in Laphroaig and Ardbeg.

Orcadian peat bogs, on the other hand, are almost entirely made up of moss and heather, giving Highland Park a more fragrant, delicate peat profile, with liquorice and gentian notes. Mainland Highland peat tends to be higher in lignins, giving more of a wood-smoked flavour.

Temperature

During its time in the cask, both the water and ethanol components of whisky evaporate over time. This lost liquid is known as the ‘Angels’ Share’.

There’s a reason why Scotland is considered the best place to make and age whisky: with cold winters and mild summers, liquid from the cask depletes at around the rate of only 2% per year. In hotter places, this evaporation process is accelerated: in Kentucky and Tennessee, the amount of liquid that disappears each year can be up to 5%, and in Bangalore, India, whisky disappears at up to an astonishing 12% per year.

Hotter temperatures also cause the whisky to take up flavours from the cask at a faster rate. Heat energises the liquid’s molecules, causing them to move around in the barrel more quickly, colliding with the oak and soaking up its character much faster.

Because of this, very young whisky matured in places like India and Taiwan can taste like much older whisky aged in Scotland: Amrut Fusion, at a mere four years old, boasts a gorgeous vanilla oakiness and has a surprisingly lengthy, spicy finish.

In colder weather, however, this entire ageing process slows to a crawl – with low to no evaporation, and whisky barely interacting with the wood, it stands to reason that not much whisky is matured in colder regions than Scotland.

Norwegian distillery Bivrost has just started maturing whisky in the Arctic circle: while they acknowledge that the cold climate will slow their ageing, they have used much smaller casks to facilitate the process. It will be very interesting to see how the final product turns out.

Humidity

In most places, as whisky ages, its alcohol content slowly decreases. This is because ethanol is more volatile than water at the same temperature, and usually evaporates at a faster rate during maturation.

However, in drier conditions, the whisky’s water content will begin to deplete more quickly. This is explained with the theory of equilibrium: since there is a high density of water vapour within the cask, and a lower density without, the vapour will attempt to achieve equilibrium by moving from inside the cask to outside. The lower the relative humidity outside the cask, the faster this reaction will happen.

In extreme cases – in very arid conditions – the water can start depleting at a quicker rate than the alcohol, causing the total ABV of the cask to rise over time. Since new make spirit is usually put into cask at between 65-80% ABV, this is less than ideal, and so higher relative humidity – for example, Scotland’s 80-90% – is generally considered favourable for ageing.

In Kentucky, the heart of whiskey production in the States, barrels are stacked from floor to ceiling in multi-level warehouses. From the bottom to top, not only does the temperature rise as much as 15 degrees Fahrenheit, but the humidity drops drastically, and casks sitting at the highest point lose water content at an staggering rate. While most distilleries blend casks from the upper and lower warehouse levels to even this out, there are some aged Bourbons that sit at impressive ABVs, such as Stagg Jr. Barrel Proof at 67.5% ABV.

Coastal influences

Distilleries by the sea – think Talisker, Old Pulteney, and Ardbeg – are often described as ‘briny’, or ‘saline’, attributed to the fact that they are matured on the coast.

This is a rather difficult concept to explain. Since salt cannot evaporate, it is odourless, and can’t penetrate a cask. The ‘salty’ smell that we perceive when we walk along the coast comes not from the sea salt itself, but from aroma compounds such as dimethylsulfide (DMS) produced by algae, seaweed pheromones called dictyopterenes, and bromophenols from fish and other sea life. These smells are carried over in the sea spray, and rest in the air around the coast.

It stands to reason that traditional dunnage warehouses by the sea let in some of these compounds, which will interact with the casks packed inside. This is particularly the case with Ardbeg, whose warehouses sit directly on the coastline and are hit by the crashing waves at high tide.

It is important to remember, however, that distilleries like Ardbeg, Old Pulteney and especially Talisker produce massive amounts of whisky, and since dunnage warehouses are expensive to upkeep, much of their spirit is aged offsite in inland warehouses. During final blending, much of the coastal climate’s effect is masked.